The introduction of the Shareholder Rights Directive (“SRD II”) across the European Union proved to be challenging for many European companies, but nowhere were the additional forward- and backward-looking remuneration proposals as controversial as the Dutch market. Of the 70 remuneration policies Glass Lewis provided voting recommendations on during the past proxy season, nine did not pass the 75% voting requirement set by the Dutch law, equaling a staggering 12.9% of total remuneration policies. Three companies in our covered database also failed to receive shareholder approval of the remuneration report, which only required a simple majority voting requirement.

The introduction of the Shareholder Rights Directive (“SRD II”) across the European Union proved to be challenging for many European companies, but nowhere were the additional forward- and backward-looking remuneration proposals as controversial as the Dutch market. Of the 70 remuneration policies Glass Lewis provided voting recommendations on during the past proxy season, nine did not pass the 75% voting requirement set by the Dutch law, equaling a staggering 12.9% of total remuneration policies. Three companies in our covered database also failed to receive shareholder approval of the remuneration report, which only required a simple majority voting requirement.

The signs of heightened scrutiny were already present in the Dutch market. The forecast made by one of the board members we spoke to during our annual engagement programme turned out to be quite prescient: ‘there will definitely be a number of companies that will encounter an unpleasant surprise. There are simply too many variables to consider. We are just trying to make sure we aren’t the ones who get surprised.’

For the companies that got their proposed remuneration policy voted down, the upcoming proxy season represents another chance, and another challenge to seek adequate shareholder – and widescale public – support for the upcoming proxy season to have their proposed remuneration policy approved by shareholders.

For the current fiscal year, companies that had their proposed remuneration policy voted down can continue to pay their management board executives under the previously approved remuneration policy, even if no changes were made to the policy.

Background to Dutch legislation; Dutch Polder Model

Under the local implementation of SRD II, Dutch companies are asked to look beyond shareholders to communicate how the broader society, including employees, consumers and the general public, has been taken into account when formulating their remuneration policies. Difficulties in such a widescale engagement outreach are to be expected, as the view from the Dutch public and legislators may contrast starkly with asset managers’ expectations.

For example, whereas most investors, internationally, believe that a significant proportion of executive pay should be at risk, the introduction of the Act on the Remuneration Policy for Financial Undertakings (“WBFO”) in mid-2016, dictated that financial institutions with operations predominantly based in the Netherlands must limit variable pay to a maximum of 20% of fixed remuneration. Other Dutch companies also experience pressure to downwardly adjust maximum opportunity, especially in terms of overall quantum.

While undoubtedly presenting challenges for Dutch companies in general, this approach is embedded in Dutch culture, for instance through the so-called Polder Model. The Polder Model is consensus decision-making, based on the acclaimed Dutch version of consensus-based economic and social policy-making in the 1980s and 1990s.

Examples of Top-of-the-Class Disclosure; Financial Institutions

It appears that the intense scrutiny that financial institutions have historically faced from a variety of stakeholders left them well-positioned to meet the enhanced disclosure and outreach requirements.

The bar was already set high in the Netherlands before SRD II came into force. ASR Nederland (“ASR”) experienced significant growth prior to the introduction of a revamped remuneration policy, which was proposed to shareholders at its 2019 AGM, and quantum was somewhat lagging compared to companies of a similar size and scope. Their outreach campaign ‘included a detailed consultation round with various stakeholders such as shareholders, employees, politicians and Dutch society as a whole.‘ While the Dutch interpretation of SRD II had yet to be transposed into Dutch law, ASRs outreach campaign provided a detailed example of how to conduct stakeholder engagement in line with the spirit of Dutch law.

Van Lanschot Kempen, at their 2018 AGM, only gained the support of less than a majority of free-float shareholders and just 62% of votes overall – enough to pass at the time, but well below the new 75% threshold. This time around, the company reported that it ‘consulted with a large cross-section of our shareholder base, proxy advisers, the Works Council, various client groups and Dutch political parties.’ Furthermore, the company reported extensively on various issues raised by the aforementioned stakeholders, such as the lack of variable remuneration, indexation, and the use of its peer group. Additionally, after considering stakeholder feedback, it has chosen not to opt for the derogation clause as incorporated into SRD II. This provision would provide the supervisory board with additional discretionary adjustment power, including the possibility to overrule the adopted remuneration policy, if deemed necessary to serve the company’s long-term interests and sustainability. Ultimately, this resulted in an approval rate of 93.72% of votes cast, well above the 75% support requirement.

Another example comes from ING Groep NV (“ING”), which at their 2018 AGM proposed an increase of up to 50% of base salary for the CEO in the form of “fixed shares” that, while not dependent on any performance conditions, would be subject to a five-year holding period and a shareholding requirement of at least one year of base salary. It’s an approach to propping up equity-based executive pay in the face of at-risk pay restrictions, such as the WBFO, that has become fairly standard in other markets – but not in the Netherlands. Following public backlash, ING saw it necessary to withdraw the proposal. In 2019, ING held extensive meetings with a number of stakeholders, including ‘the Dutch Central Works Council, representatives of Dutch trade unions, the Advisory Council of ING Netherlands, trade bodies and regulatory and governmental authorities including the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and European Central Bank. A number of ING Group’s largest institutional shareholders, together holding approximately 24% of ING Group’s share capital, were consulted as well as proxy advisory firms and Dutch shareholder advocacy groups.’ The conversations appear to have been productive: ING’s remuneration policy was approved with broad support, equal to 92.77% of votes cast.

Disclosure Across the Broader Dutch Market

Financial institutions were not the only companies to report in line with the spirit of the social acceptance requirement. Koninklijk KPN (“KPN”) disclosed they consulted ‘shareholder representatives, proxy advisory firms, external remuneration advisors, peer companies, the Central Works Council and the members of the Board of Management and Supervisory Board themselves.’ Furthermore, KPN highlights that the proposed remuneration policy also considers the focus on financial- and non-financial targets under the STI and LTI incentive plans, including the emphasis on sustainable long-term business performance.

However, not everyone has gotten on board. When SRD II was transposed into Dutch law at the end of 2019, several smaller companies simply stated that ‘social acceptance’ has been considered, while failing to deliberate on how this was done. From very early on it was clear that the market did not appreciate such limited disclosure. Eumedion, the Dutch corporate governance forum, raised concerns about the November 12, 2019 special meeting of Intertrust NV. Among other issues, Eumedion considered Intertrust’s assessment of social acceptance to be an incorrect interpretation of the Dutch implementation bill regarding SRD II. At the very least, various stakeholders should be considered.

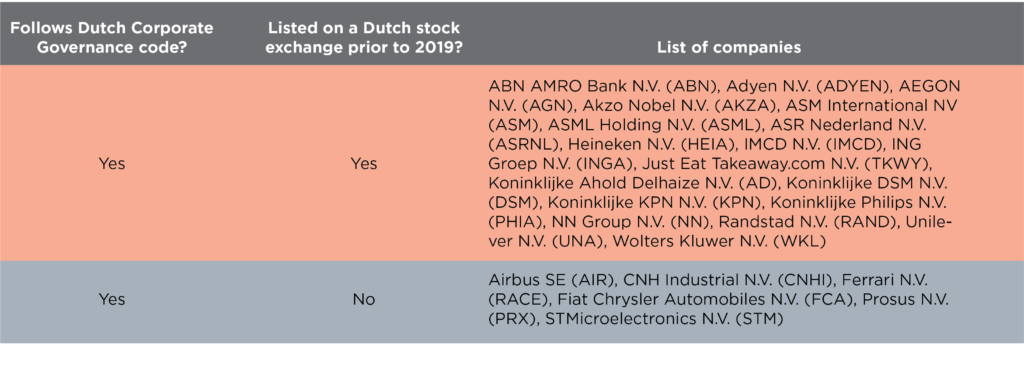

Dual Listed Companies; Social Acceptance Disclosure

The situation is more complicated for companies with dual listings in other markets with less stringent governance regulations. One aspect where this manifests is the utilisation of loyalty shares. Permissible under Dutch law, their use is very rare for companies that are incorporated and listed only in the Netherlands – however, companies with a dual listing, or that are merely incorporated in the Netherlands, may employ such a share structure. For example, Ferrari, CNH Industrial and Fiat-Chrysler each have a dual-voting structure where share that have been continuously owned for an interrupted period of three years are eligible to receive additional special voting shares on a one-to-one basis. In the case of Prosus NV, if Naspers’ shareholding in the Company drops below 50% plus one vote, their A1 ordinary shares will be converted into A2 ordinary shares and subsequently carry 1,000 votes per share.

Acknowledging that dual listed companies must serve a multitude of different views, it was particularly interesting to see how these companies would tackle the requirement on social acceptance disclosure. We note that the Dutch entity of the Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield group (“URW NV”) was subject to their first vote on remuneration at the 2020 AGM, as there was no such vote at their 2019 AGM. Initially, disclosure on social acceptance was very limited to the extent that “since there has not been any vote by the GM on the Existing Remuneration Policy and no advisory vote on the Company’s remuneration report since the listing of the Company’s class A shares, the Remuneration Policy described below cannot (and therefore will not) include a description of how those votes and relevant shareholders’ perspectives in this respect have been taken into consideration.“ Eventually, and well before their 2020 AGM, the company made several clarifying changes to their remuneration policy, mainly to improve disclosure. As such, URW NV emphasised that it is “committed to extensive and proactive consultation with shareholders”, including “dialogue between management and the Works Councils in the various countries where the Group operates”.

Not all dual listed entities benefitted from an initial learning period like the one URW NV went through. STMicroelectronics received the most severe shareholder disapproval of the management board remuneration policy, with only 50.19% of votes cast in support of their remuneration policy. The result was perhaps unsurprising: approximately 37.8% of shareholders had voted against a proposed equity grant to the CEO at the prior year’s annual general meeting. At the very least, a discussion on stakeholder interests – and in particular a discussion on how the board considered and responded to shareholder opposition – would seem appropriate, in line with Dutch requirements.

Dual Listed Companies; Quantum

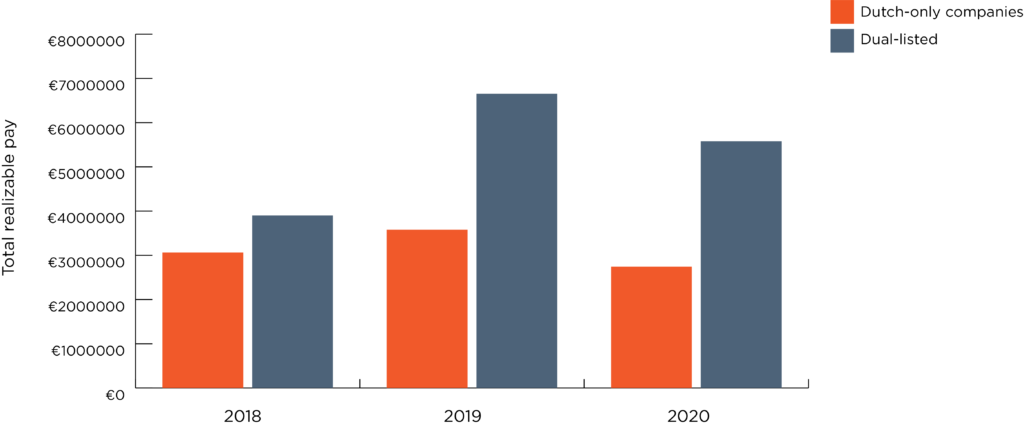

Having to manage multiple constituencies isn’t the only reason that dual-listed companies have faced close scrutiny on their remuneration programmes. Another factor is that they tend to pay significantly more money than Dutch companies, with the average difference in realizable pay exceeding €2 million for each of the past two years. It is somewhat understandable that these companies receive intense scrutiny from Dutch stakeholders, where US based investors might not identify such quantum as controversial.

Scrutiny on Quantum; US based peers

During the Dutch 2020 proxy season, the inclusion of U.S.-based companies in the Dutch-listed companies benchmarking peer groups was a point of contention. Pay practices differ significantly between Continental Europe and the U.S., raising questions when Dutch companies choose to benchmark against these companies. Dutch society generally assigns great value to its status as an egalitarian country. Consequently, high quantum is closely scrutinised.

Considering the aforementioned, Wolters Kluwers’ remuneration benchmark included 8 spots for U.S. based companies, out of 18 companies. Consequently, the CEO’s pay significantly outpaces those of its Dutch market cap peers and European industry peers. While 61% of the company’s revenues have come from North America, as well as the fact that the company’s CEO was recruited internally from the U.S., only 50.27% of votes cast supported the remuneration policy, failing to meet the 75% threshold for approval. Regarding social acceptance disclosure, Wolters Kluwers generally aligns with Dutch market practice. However, shareholders may have expected increased disclosure on aspects like the stakeholder engagement process, as well as the inclusion of E&S metrics under STI or LTI plans. Ultimately, it may not be a matter of disclosure or explanation – building local support may instead require scaling back on overall quantum to reflect local expectations.

Like Wolters, Koninklijke Philips N.V. (“Philips”) also incorporates U.S. based peers in its remuneration framework. Philips currently has significant operations in the U.S., equal to approximately 36% of total sales. However, Philips’ remuneration policy limits US benchmark peers to a maximum of 25% of the group. Philips and Wolters Kluwer have similar quantum and maximum opportunity under their remuneration framework, yet Philips received 91.37% support of votes cast. While certain nuances apply, an excessive amount of U.S. based peers appears to be a matter of controversy.

Scrutiny on Quantum; Absolute Payouts

Dutch quantum generally falls below that of European counterparts, which can be attributed to local pressure to limit pay. And even within the context of lower base salaries compared to other markets, scrutiny of quantum remains tight, with large absolute bonus payouts providing another recipe for shareholder opposition.

Bonus concerns led Flow Traders NV (“Flow Traders”) to receive shareholder pushback. The company’s incentive plan includes aggregate caps on variable pay (35% of profit in any year, with a maximum of 15% for the management board), but there are no limits on individual allocations from the variable pool. Although base salary is capped at €94,608, the tradeoff is a substantial incentive opportunity. Shareholder concerns about this structure are exacerbated by the company’s starkly increased revenues and profits in Q1, where profit rose more than 10 times from last year, directly capitalising on the volatile market conditions at the time. Ultimately, Flow Traders only received support of 56.01% of votes cast, and the remuneration policy of the management board was not supported by its shareholders.

In the past year, BESI Semiconductor (“BESI”) continued its practice of granting discretionary bonuses comprising 120,000 shares, with this grant valued at €2,270,400. According to the company, the awards were made “

High remuneration levels at AMG Advanced Metallurgical Group N.V. (“AMG”) stem mainly from the awards under the company’s FY2014-2016 long-term incentive plans, which led 2017-2019 total realisable pay to average €12.7 million, in part reflecting notable increase in the share price since grant (from €6.76 per share on December 31, 2014 to €21.7 per share on December 30, 2019, with higher peaks along the way). AMG only received support from 48.66% of votes cast.

Scrutiny on Structural Concerns

Dutch companies can face scrutiny for a variety of reasons beyond peer group construction and quantum levels. While structural concerns are rare, high standards across the market mean that outlier structures stick out all the moreso, attracting shareholder attention.

Vastned Retail NV (“Vastned”), a retail property company for ‘venues of premium shopping’, experienced concentrated shareholder dissent from of one of its major shareholders, Aat van Herk, who approximately owns 26% of issued share capital. Van Herk observed that over a ten-year period, rental incomes and dividends had halved while costs doubled. With quorum at 56.3% of share capital, van Herks’ disapproval led to the rejection of the supervisory board remuneration policy, management board remuneration policy, ratification of supervisory board acts and the authority to repurchase shares.

Shareholders of C Tac-Align on the other hand did not appreciate the generally positive direction of travel of the proposed remuneration policy. While the company moved toward standard market practice by setting maximum incentive opportunity as a percentage of base salary going forward, shareholders did not appreciate the rather vague performance conditions. Ultimately, their management board remuneration policy only received approval of 43.83% of votes cast.

COVID-19 Impact

Like other markets, the Netherlands has been hit by the coronavirus, requiring companies to transition from physical to virtual general meetings with little warning. Most companies in the Netherlands are discouraging their investors from physical attendance at AGMs; postal, electronic, and proxy votes are possible. According to Eumedion’s evaluation of the 2020 AGM season, a total of 41 ‘virtual only’ AGMs were held by Dutch companies, which corresponds to 43% of Dutch companies. As the governance of most Dutch companies already are largely in line with best practice according to the Dutch Corporate Governance Code, again, focus was mainly placed on remuneration practices and quantum, especially considering the impact of possible government payoffs and staff layoffs.

In the days preceding its 2020 AGM, Heineken NV (“Heineken”) communicated that for FY2020 no bonuses would be paid, and salaries would be cut by 20%. In the first quarter of 2020 the beverage brewer sold 2.1% less beer than a year before. While the company was subject to an Eumedion alert, which set out concerns regarding the use of U.S. based peers in its remuneration benchmark peer group, relatively high maximum opportunity at 820% of base salary, and the fact that the matching share plan is not based on performance, the steps it took in response to the pandemic appear to have resonated: the company received support of 96.31% of votes cast for the proposed management board remuneration policy.

Furthermore, Randstad NV (“Randstad”) has warned shareholders of tougher times ahead, scrapping management bonuses. While Randstad beat first-quarter expectations, with sales falling less than initially expected, the more challenging forecast prematurely ended executives’ opportunity for additional rewards beyond fixed salary for the 2020 fiscal year.

Looking Ahead

We expect the backward-looking remuneration report to remain an area of significant focus in 2021 and beyond. It is likely that the initial leeway granted by shareholders will end, with the bar for disclosure increasing. The expectation is that prospective metric disclosure and retrospective performance target disclosure under incentive plans will become market practice, with prospective disclosure of both metrics and performance targets being best practice.

With shareholder scrutiny likely to increase, companies that did not receive 75% approval of their management board remuneration policy in 2020 face a stark challenge for 2021. How to overcome that challenge will depend on the company’s specific circumstances, reinforcing the need for outreach –boards will have to interrogate the causes of shareholder concern.

That very outreach would appear to be a good place to focus. Whether shareholders are concerned about quantum or disclosure or something else entirely, one engagement quote springs to mind: ‘There will definitely be a number of companies that will encounter an unpleasant surprise. There are simply too many variables to consider. We are just trying to make sure we aren’t the ones who get surprised.’

For more information on proxy season 2020 across Europe, and around the globe, see our series of Proxy Season Reviews.